|

One of the many joys of field research in Madagascar is the culinary experience. From the crowded streets of the capital city Antananarivo to the fresh fruit for purchase in coastal cities and fireside meals at camp, Malagasy food is a treat. Our team works hard day and night to collect data, so we certainly need quality nourishment to fuel the research. Thankfully, we work with two amazing camp caretakers/ cooks, Gabby and Seraphin, who work tirelessly to ensure that we are well-fed. Cooking at our camp presents quite the challenge. Our camp is about a five hour hike from the nearest village, and further still from a market. We employ the help of countless porters to carry our food and other necessary supplies up the steep mountain paths. From there, Gabby and Seraphin manage the kitchen and plan our meals so that there is enough to go around for the ~15 of us until the porters deliver the next round of supplies a few weeks later. After waking up at around 4am to stoke the campfire where they cook all meals, the duo fetches water from the nearby river for boiling the rice. They are often also the last to retire to their tents at night. I am endlessly grateful for their hard work and dedication to provided clean, nutritious meals for everyone. Madagascar has the highest per capita rice consumption in the world so, naturally, we eat rice for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. It is shocking how quickly the we can work our way through a 60kg bag of rice. The rice is usually accompanied by beans, and sometimes by vegetables or meat, and we often add sakay (Malagasy hot sauce) for variety. Meals are always finished off with ranon'apango (tea made with burnt rice from the bottom of the pot). Admittedly, I squirrel away a supply of snacks in my tent for when my sweet tooth gets the better of me, but I truly love the camp food. My favorite part of food at camp is that it is always a communal experience. We all eat together in a "family style" for meals, which is an excellent opportunity for talking about research ideas and problems, sharing stories, and bonding. I also have many fond memories of roasting plantains over the campfire for a post-work snack. I am thankful for the nutritious food that we are lucky to eat while conducting fieldwork. It is critical to note that not everyone has access to enough high-quality food. Over 1.3 million people in Madagascar face acute food insecurity and ~40% of Malagasy children face chronic malnutrition (source: World Food Programme). Members of our interdisciplinary Bass Connections team and partners at the Duke Lemur Center are working to better understand food insecurity and malnutrition in the SAVA region of Madagascar, where we conduct research. Beyond researching these topics, our partners are providing trainings in gardening, chicken husbandry, and other important measures for reducing food insecurity. See here for suggested further reading.

0 Comments

A behind-the-scenes look into our new video! Research in the rainforests of Madagascar is about more than data. Nevertheless, I do have to condense the work my colleagues and I do into numbers that I then use for statistical analysis. This task is important for testing hypotheses and determining patterns that help explain ecological processes. But, given the limitations of data and statistics for telling a story, how can we convey nuances of nature and ecological relationships too complex to distill into numbers fit for an analysis?

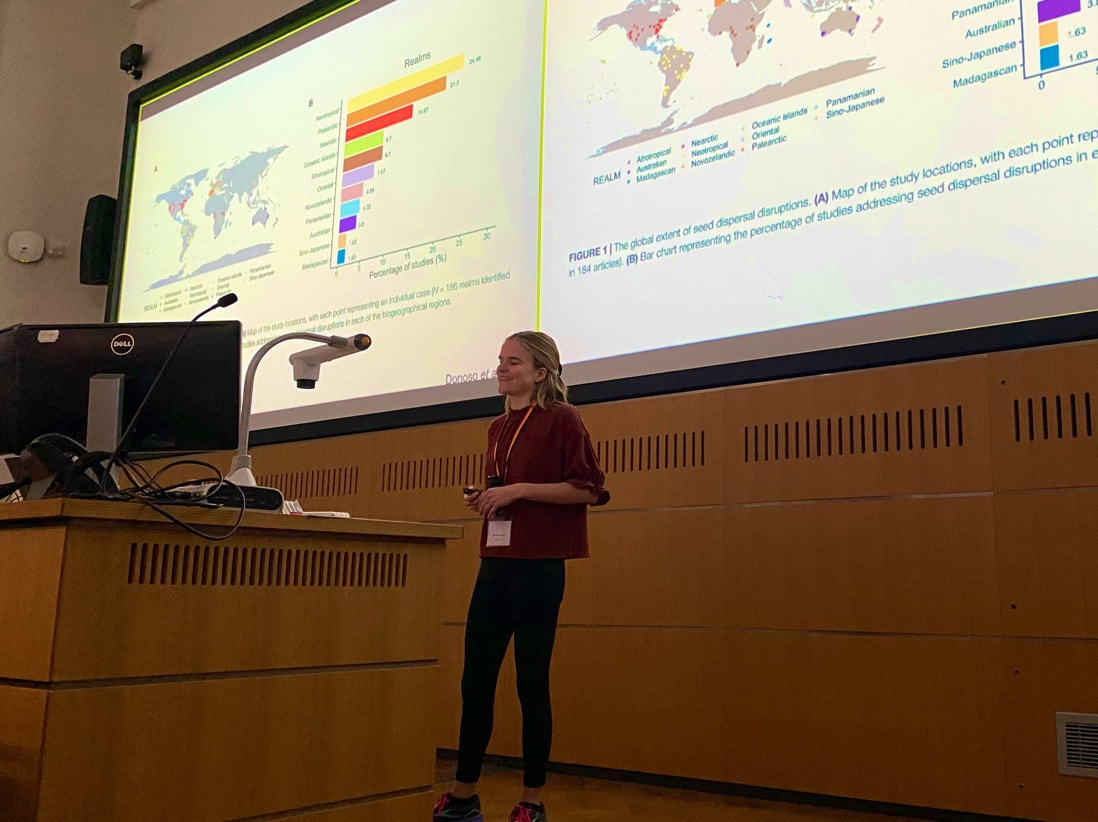

Conferences: a rewarding aspect of life as an ecology student and researcher. As a fourth year PhD student with several field seasons under my belt, I have begun to work with my collaborators to test our hypotheses and analyze our data. Although I am a self-proclaimed "field researcher", the important and time-consuming task of data analysis occurs not under rainforest canopies, but at a desk chair and behind a computer screen. Lately, I have been spending countless hours toiling over R scripts. This isn't to say that writing code and conducting statistical analysis isn't thrilling in its own right. It is also far from the "easy" part of research. Crashing my computer, de-bugging R scripts, and re-running analyses after realizing a critical error can be deflating. But it is well worth the eventual elation of turning the 1s and 0s of scientific data into a figure. Analysis is also an iterative process. In addition to seeking out rounds of feedback from my co-authors, I am eager for feedback from broader scientific communities. Luckily, attending conferences allows me to venture beyond my desk chair while seeking feedback on projects. Critical feedback on research is a key motivating factor for attending conferences. Sharing the story of my research and its conservation importance, building community with other scientists, and learning about inspiring projects being conducted around the world are equally important benefits of conferences. Of course, there is the added bonus of traveling to explore a new area. This past week, I had the opportunity to present my research at the Student Conference on Conservation Science (SCCS) in Cambridge, UK. Unlike typical academic conferences, this event is targeted at students and early career researchers. SCCS is small and global, with ~150 delegates from ~50 countries. Throughout the week, I was inspired to meet many brilliant researchers and practitioners working on projects all over the world. I learned about topics ranging from raptor conservation to global soil carbon dynamics, from illegal wildlife trafficking to using fungi to advance rainforest restoration. I also enjoyed participating on a workshops on research ethics and academic publishing. It was motivating to be a part of a group of people who all care deeply about conservation and to see the diversity of innovative conservation approaches. While SCCS is just one stop on my conference "circuit" as I head towards the final year of my PhD, it certainly made a mark. I left the conference feeling purposeful and re-energized to dive back into my data analysis.  Presenting preliminary results for one of my PhD chapters at the Student Conference on Conservation Science in Cambridge, UK. Presenting preliminary results for one of my PhD chapters at the Student Conference on Conservation Science in Cambridge, UK. Exploring the beautiful city of Cambridge was also a perk!

During my first research trip to Madagascar in 2017, I yearned to understand the jokes my colleagues told around the campfire, to contribute my own stories and add to the laughter. As a young American woman with elementary language skills, I struggled to find my place on the field team. Thankfully, my colleagues patiently taught me Malagasy words and phrases necessary for life in the forest: hazo (tree), orana (rain), noana (hungry), etc. These basics went a long way in empowering me to learn more about the forest. I also began to build valuable friendships with my teammates. Since then, I have returned to Madagascar on four additional trips to conduct research on the island's unique biodiversity. While there, I am immersed in the Malagasy language. Along with French, Malagasy is the official language of the island. With ~28 million native speakers, Malagasy is the most commonly spoken language in Madagascar, especially outside of major cities. Malagasy's 18 dialects pose a challenge to eager language students such as myself. But, no matter where I travel, I am met with generous people willing to help me on my language learning journey.

Where is the largest community of lemurs outside of Madagascar? Durham, North Carolina. As a Durham resident studying plant-lemur interactions, this surprising fact is exceptionally convenient (although hardly coincidental, as opportunities for lemur research were a motivating factor for my move to NC). Nestled in the Duke Forest, The Duke Lemur Center (DLC) is home to over 200 lemurs across 13 species. With a mission to "advance science, scholarship, and biological conservation through non-invasive research, community-based conservation, and public outreach and education", the DLC immediately captured my fascination. As a PhD student with a background in field biology in Madagascar, I first became involved with the DLC's SAVA conservation program. DLC SAVA is the branch of the DLC that is based in Madagascar and focuses on biodiversity conservation. I work with DLC SAVA staff and many local collaborators to study wild lemurs, plants, and their interactions in northeast Madagascar (see previous blog posts for more details). While I love field research, logistical challenges and cryptic, unhabituated (wild, not familiar with human presence) lemurs pose limitations to the experimental design needed for the seed dispersal questions that I am keen to ask. For example, I am interested in how both plant and lemur characteristics influence the likelihood of lemur-dispersed seeds resulting in new plant recruits. Is is possible that not only species differences, but also individual traits (sex, age, weight) affect seed dispersal. But these questions remain unanswered, partly because these traits are difficult and resource-intensive to characterize in wild lemur seed dispersers. Luckily, the DLC presents a unique opportunity to study seed dispersal in a controlled environment where I have access to data on individual lemur traits. After developing an experiment to assess the drivers of seed dispersal outcomes, acquiring necessary permits and approvals, and connecting with several brilliant undergraduate research assistants, I dove head-first into my first experience with captive animal research. I was lucky that three skilled undergraduates joined the seed dispersal team: Allie Monahan from NC State, Borna Zareiesfandabadi from UNC Chapel Hill, and Dedriek Whitaker from Duke. Together, we fed lemurs seeds from common agricultural plants (kiwis, dragonfruit, melon, etc.... a tasty treat!) and observed the lemurs until they gifted us with their poop samples. My team and I spent hours diligently sorting through the samples to extract and measure seeds. It's a good thing that we aren't squeamish! Each lemur-passed seed was placed in a Petri dish under different experimental treatments. We then monitored seeds to identify if and when each individual germinated. In total, we collected and measured over 6,000 seeds dispersed by eight lemur species. Importantly, we know which lemur individual dispersed each seed, enabling us to ask questions about how individual traits affect seed dispersal outcomes. Collecting such a wealth of detailed data would not have been possible without the hard work, creativity, and passion of Allie, Borna, and Dedriek. Captive animal studies come with their own limitations. For example, the Malagasy plant species that lemurs typically consume in the wild are not available for use in captive animal studies in Durham. There are therefore tradeoffs between experimental control and ecological relevancy. To address this challenge, we hope to compare data from the DLC to data to a parallel field study with wild lemurs in Madagascar. Stay tuned for forthcoming results!

Forest field team members at camp (not everyone present). Photo credits to Jane Slentz-Kesler. Forest field team members at camp (not everyone present). Photo credits to Jane Slentz-Kesler. Sitting in my office in Durham after an afternoon of wading deep into data analysis, I often find myself daydreaming about fieldwork in COMATSA, a community-managed protected area in northeastern Madagascar. I reminisce about evenings sipping ranon’apango (Malagasy burnt rice tea), roasting plantains over the campfire after a sweaty day hard at work, and joking with the team over dinner. While I love field research for the science, many other aspects of camp life are what bring me the greatest joy. Undoubtedly, my favorite part of research is being part of a team. In COMATSA, I am privileged to work in a large, multidisciplinary field team with colleagues who have become dear friends. We are composed of students and researchers from the local forest management association, University of Antananarivo, Centre Universitaire Régional de la SAVA, expert consultants and guides from nearby Marojejy National Park, Duke Lemur Center, and Duke University. Due to the interdisciplinary nature of our work and the large size of our team (~20 people), we conduct research in several subteams:

Everyone on the team contributes a tremendous amount of expertise. We all work together to ask interesting questions, collect data, and think critically about ecological problems. Importantly, we also share laughter, support one another through challenges, and celebrate successes. Research is a team effort, and I am grateful for the community we have built together.

|

|